Trip.com: First Step towards Cloud Native Security

TL; DR

This post shares our explorations on cloud native securities for Kubernetes

as well as legacy workloads, with CiliumNetworkPolicy for L3/L4 access

control as the first step.

- TL; DR

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Access control: from requirements to a solution

- 3 Rollout into production

- 4 Discussions

- 5 Conclusion and future work

- References

Several previous posts have witnessed the evolving of our networking infrastructures in the past years:

- Ctrip Network Architecture Evolution in the Cloud Computing Era, 2019

- Trip.com: First Step towards Cloud Native Networking, 2020

- Trip.com: Stepping into Cloud Native Networking Era with Cilium+BGP, 2020

As a continuation, this post shares our explorations on cloud native securities. Specifically, we’ll talk about how we are deploying access controls in Kubernetes with Cilium network policies in a consistent way with legacy infrastructures.

Note: IP addresses, CIDRs, YAMLs and CLI outputs in this post may have been tailored and masked, which are only for illustrating purposes.

1 Introduction

Some background knowledge about access control in Kubernetes is necessary before diving into details. If already familiar with those stuffs, you can just fast-forward to section 2.

1.1 Access control in Kubernetes

In Kubernetes, users can control the L3/L4 (IP/port level) traffic flows of applications with NetworkPolicies.

A NetworkPolicy describes how a group of pods should be allowed to

communicate with other entities at OSI L3/L4,

where the “entities” here can be identified by a combination of the following 3 identifiers:

- Other pods, e.g. pods with label

app=client - Namespaces, e.g. pods from/to namespace

default - IP blocks (CIDRs), e.g. traffic from/to

192.168.1.0/24

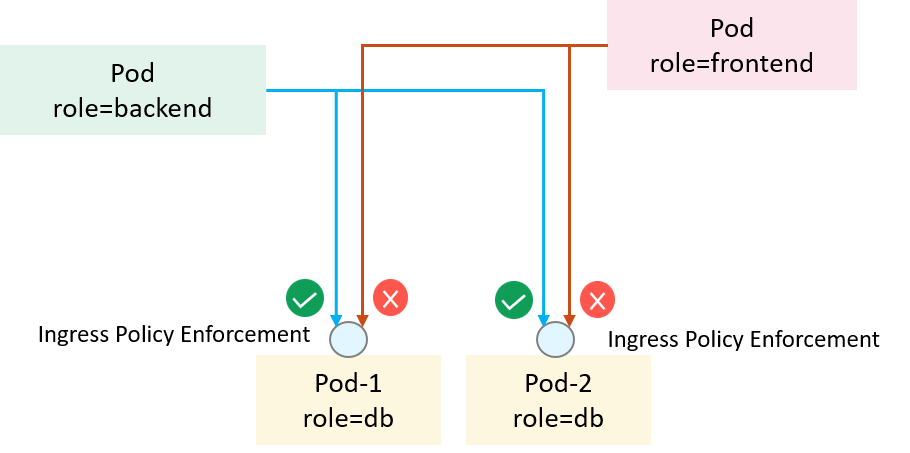

An example is depicted in the below,

Fig 1-1. Access control in Kubernetes with NetworkPolicy

We would like all pods that labeled role=backend (client-side)

to access the service at TCP/6379 of all pods with label role=db (server-side),

and also other clients not in this spec should be denied. Below is a minimal

NetworkPolicy to achieve the purpose (assuming client & server pods in the

default namespace):

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: network-policy-allow-backend

spec:

podSelector: # Targets that this NetworkPolicy will be applied on

matchLabels:

role: db

ingress: # Apply on targets's ingress traffic

- from:

- podSelector: # Entities that are allowed to access the targets

matchLabels:

role: backend

ports: # Allowed proto+port

- protocol: TCP

port: 6379

While Kubernetes defines the NetworkPolicy model, it

leaves the implementation to each networking solution,

which means that if you’re not using a networking solution that supports

NetworkPolicy, the policies you applied would have no effect.

More information about Kubernetes NetworkPolicy, refer to Network Policies [1].

1.2 Implementation and extension in Cilium

Cilium as a Kubernetes networking solution implements as well as extends

the standard Kubernetes NetworkPolicy. To be specific, it supports three kinds

of policies:

NetworkPolicy: the standard Kubernetes network policy, controlling L3/L4 traffic;CiliumNetworkPolicy(CNP): an extension of the standard KubernetesNetworkPolicy, covering L3-L7 traffic;ClusterwideCiliumNetworkPolicy(CCNP): namespace-less CCNP

An example of the L7 CiliumNetworkPolicy:

apiVersion: "cilium.io/v2"

kind: CiliumNetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: "rule1"

spec:

description: "Allow HTTP GET /public from env=prod to app=service"

endpointSelector:

matchLabels:

app: service

ingress:

- fromEndpoints:

- matchLabels:

env: prod

toPorts:

- ports:

- port: "80"

protocol: TCP

rules:

http:

- method: "GET"

path: "/public"

You can also find a more detailed CCNP example in our previous post Cilium ClusterMesh: A Hands-on Guide [3].

1.3 Challenges in large deployments

As seen above, with NetworkPolicy/CNP/CCNP, one can enforce L3-L7 access controls inside a Kubernetes cluster. However, for large deployments in real clusters with critical businesses running in, far more stuffs need to be considered, just naming some of them below:

-

How to manage policies, and what’s interface to end users (developers, security teams, etc)?

- The “laziest” way to manage policies may be creating a git repository and putting all the raw policy yamls there, but -

- Application developers in most cases do not have access to Kubernetes infrastructures as we (infra team) do, so we can’t rely on them to manipulate raw yaml files like we do.

-

How to perform authentication and authorization when manipulating a policy?

Enter the 4A model (Accounting, Authentication, Authorization, Auditing). Such as,

- How to validate a (human) user (developer, admin, etc)?

- Who can request a policy for what resource (applications, databases, etc)?

- Who is reponsible for approving/rejecting a specific policy request?

- Auditing infrastructures, vital for a security solution.

-

How to handle cross-boundary accessing? E.g, direct pod-to-pod traffic cross Kubernetes clusters.

In a perfect world, all service accessing converge to cluster boundaries, and all cross-boundary traffic goes through some kind of gateways, such Kubernetes Egress/Ingress gateways.

But most companies in reality do not have so clean an infrastructure. Reasons come from many aspects, such as

- costs (effectively involves duplicating the entire infra in each cluster)

- compatibility with legacy (technically out-of-date but business critical) infrastructures

All these stuffs result in direct pod-to-pod traffic cross clusters, which inherently involves us to address the Kubernetes multi-cluster problem.

-

How to manage legacy workloads (e.g. VM/BM/non-cilium-pods)?

For companies which have evolved more than a decade, it’s highly likely that there is not only direct cross-boundary traffic, but also legacy workloads, such as VMs in OpenStack, BM system, or Kubernetes pods powered by networking solutions other than Cilium.

Some of these may be transient, e.g. migrating non-cilium-powered-pods to Cilium-powered cluster, but some may not, such as VMs still can not be replaced by containers in certain scenarios.

So a natural question is: how to cover those entities in your security solution?

-

Performance considerations

Performance should be one of the topic considerations for any tech solution. In terms of a security solution, we should care about at least:

- Forwarding performance: will the solution cause severe performance decrease?

- Policy taking-effect time (latency)

-

Logging, monitoring, alerting, observability, etc

Be more familiar with your system than your users, instead of being called up by latter at midnight.

-

Downgrade SOP

Last but not least, what to do when part or even all of your system misbehave?

1.4 Organization of this post

The remaining of this post is organized as follows:

- Section 2 illustrates how we designed a technical solution piece by piece;

- Section 3 describes our rolling-out strategies in practice;

- Section 4 discusses some important technical questions in more depth;

- Section 5 concludes this post.

2 Access control: from requirements to a solution

In this section, we’ll see how we’ve designed a solution from bottom to up that meets the following requirements:

-

Access control over hybrid infrastructures

- Support Kubernetes (main case), OpenStack, Baremetal, etc

- Support on-premises infrastructures as well as infrastructures on public cloud

- Support cross-cluster direct traffic

-

Evolvable architecture

- Multiple policy enforcer support

-

Support L3-L7 access control

-

High performance

2.1 Policy enforcement in a single cluster

Starting from the simplest case, consider the access control in a standalone Cilium-powered Kubernetes cluster.

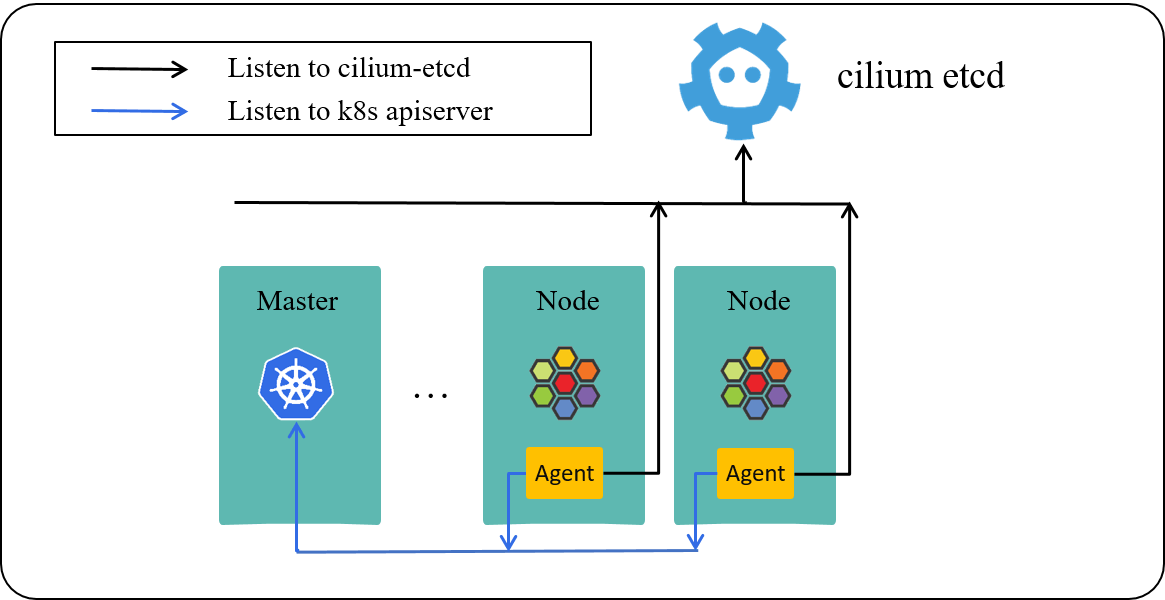

As the logical architecture depicted below, Cilium agent on each Kubernetes worker node listens to two resource stores:

Fig 2-1. A Kubernetes cluster powered by Cilium [3]

- Kubernetes apiserver (in front of k8s-etcd): for watching CNP/CCNP etc, resources

- KVStore (cilium-etcd): for watching identities of pods (and other cilium metadata) of the whole cluster

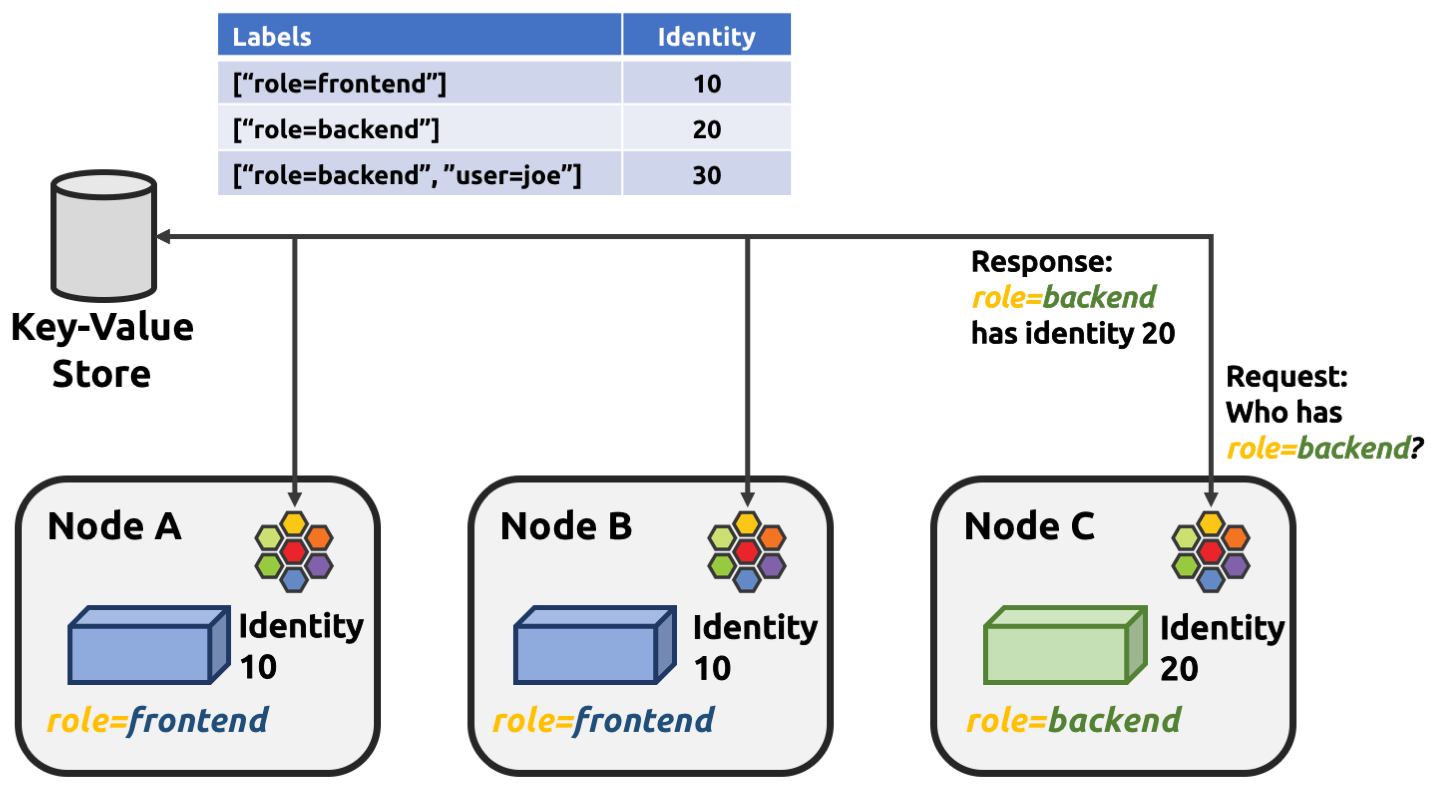

In this standard single-cluster setup, the native CNP/CCNP would be enough for policy enforcement, in that the cilium-agent on each node caches the entire active identity space of the cluster. As long as clients come from the same cluster, each agent would know their security identity by looking up its local cache, then decide whether to let the traffic go:

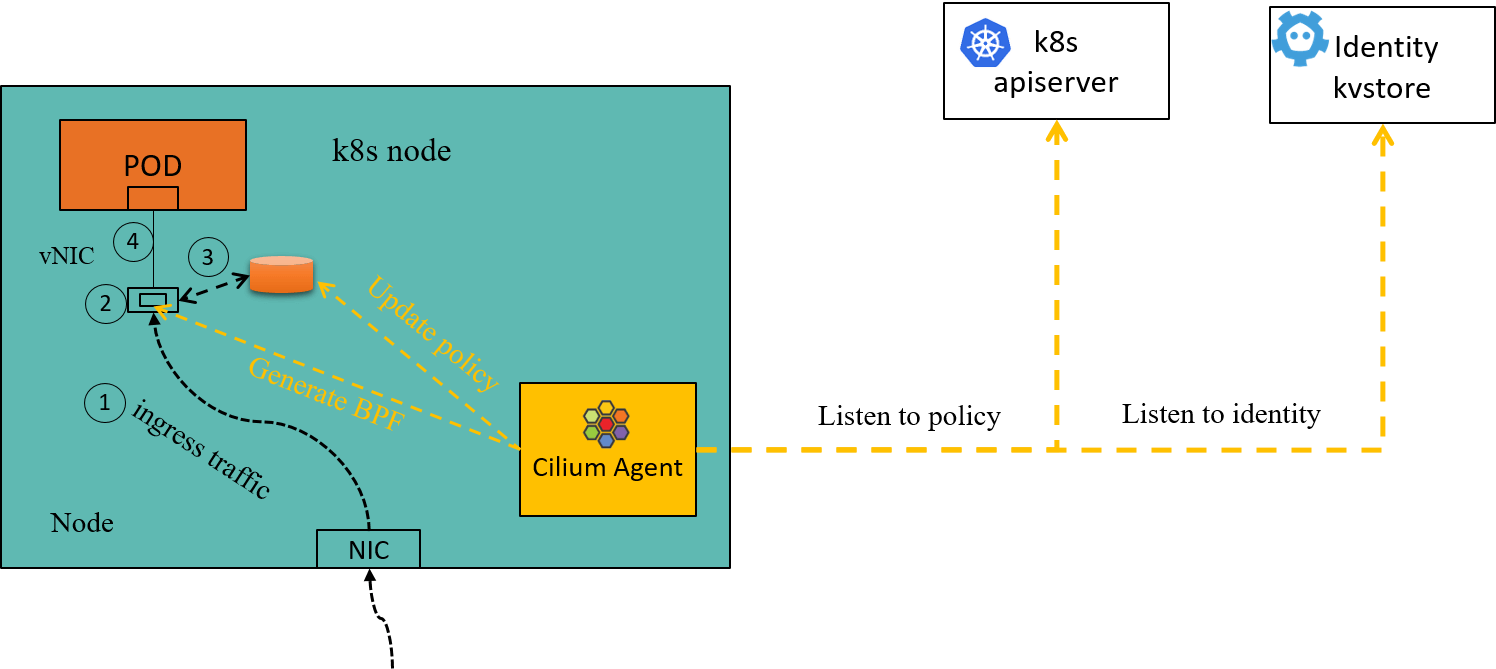

Fig 2-2. Ingress policy enforcing inside a Cilium node

Some code-level details can be found in our previous post [9]:

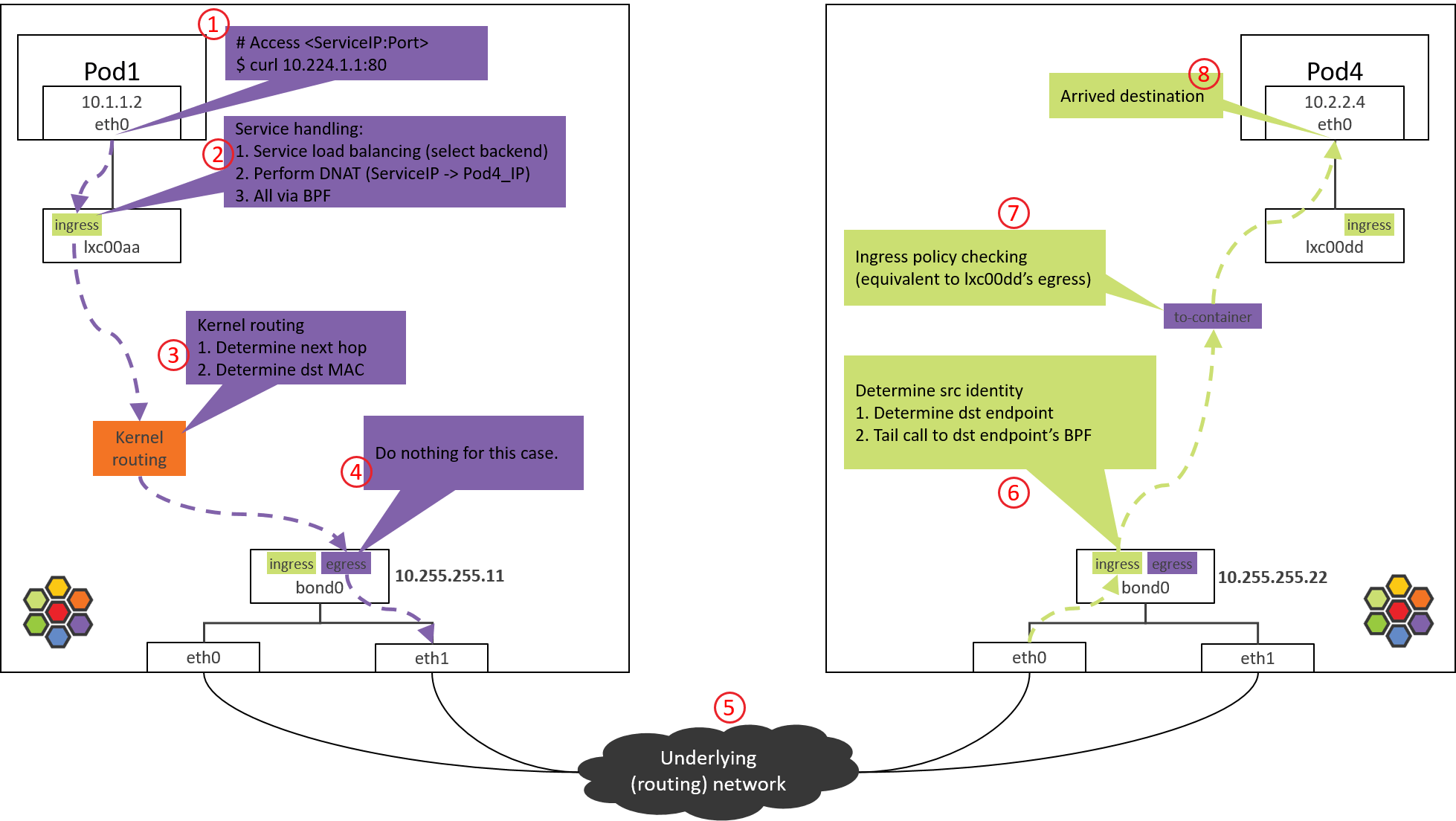

Fig 2-3. Processing steps (including policy enforcing) of pod traffic in a Cilium-powered Kubernetes cluster [9]

2.2 Policy enforcement over multiple clusters

Now consider the multi-cluster case.

Imagine that the server pods reside in one cluster, but the client pods scatter over multiple clusters, and the clients access the servers directly (without any gateways).

Kubernetes best practices would suggest avoiding this setup, instead, always do cross-cluster accessing via gateways. But real world, crucial business requirements and/or technical debts often creep to the architecture.

2.2.1 ClusterMesh

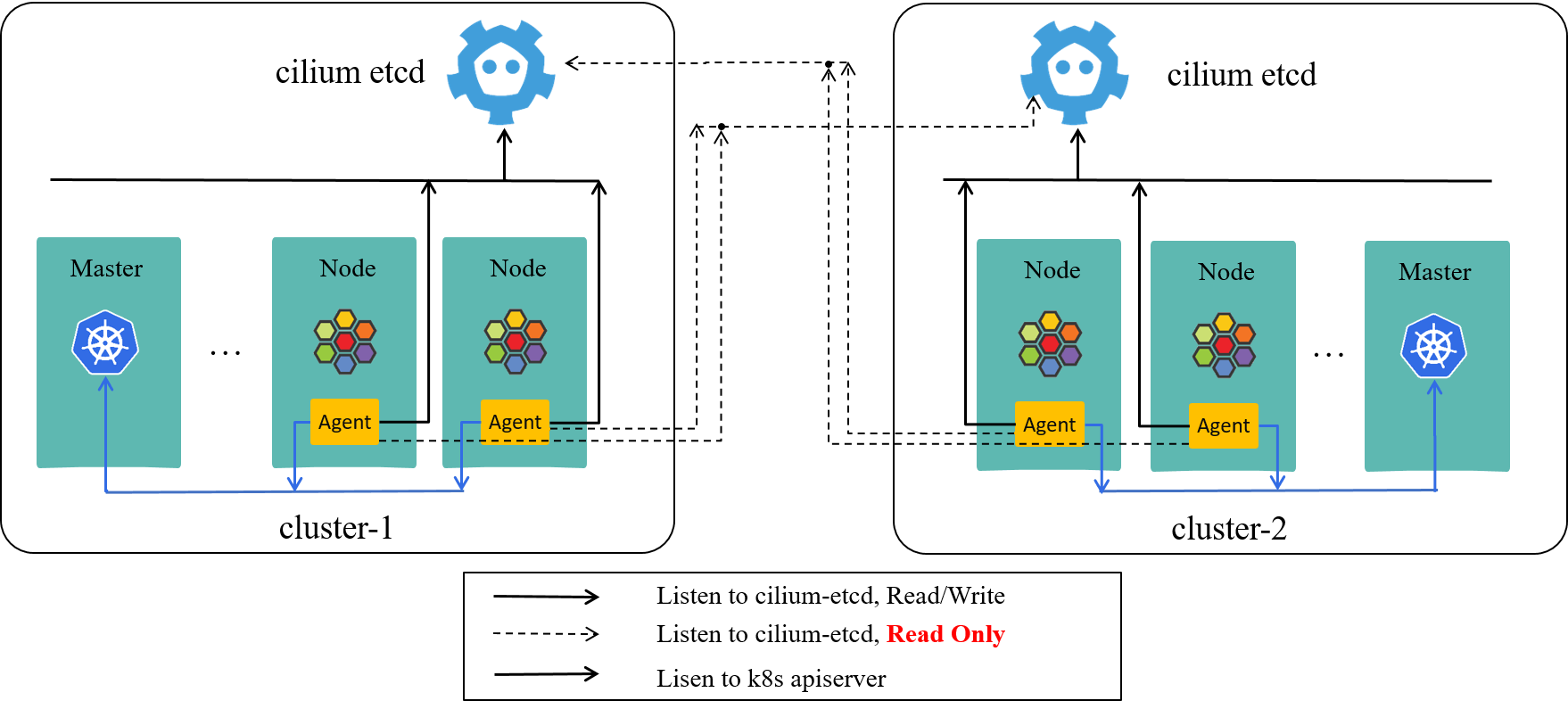

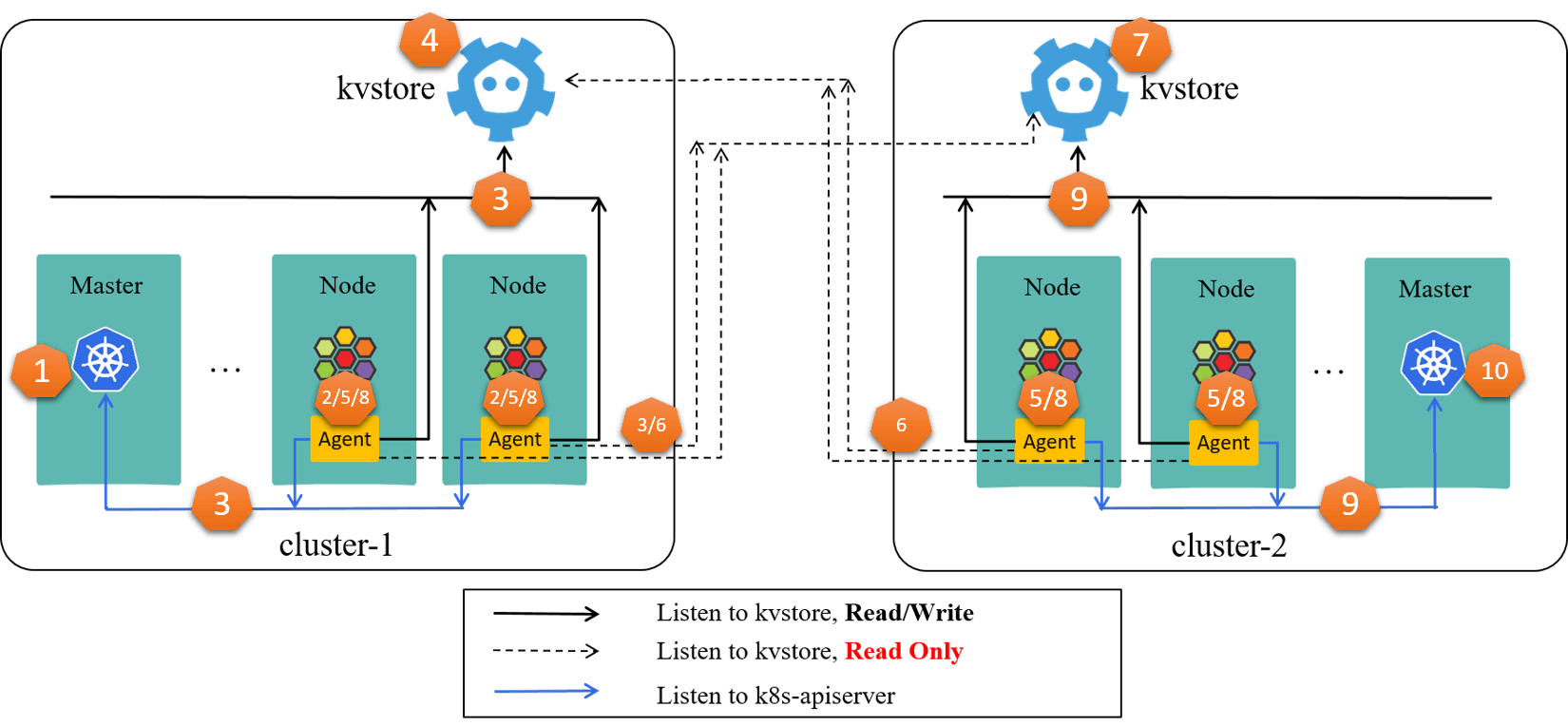

Cilium ships with a built-in multi-cluster solution called ClusterMesh. Basically, it configures each cilium-agent to also listen to the KVStores of the other clusters. In this way, each agent gains the security identity information of pods in the remote clusters. Below is the two-cluster-as-a-mesh case:

Fig 2-4. ClusterMesh: each cilium-agent also listens to the KVStores of the other clusters [3]

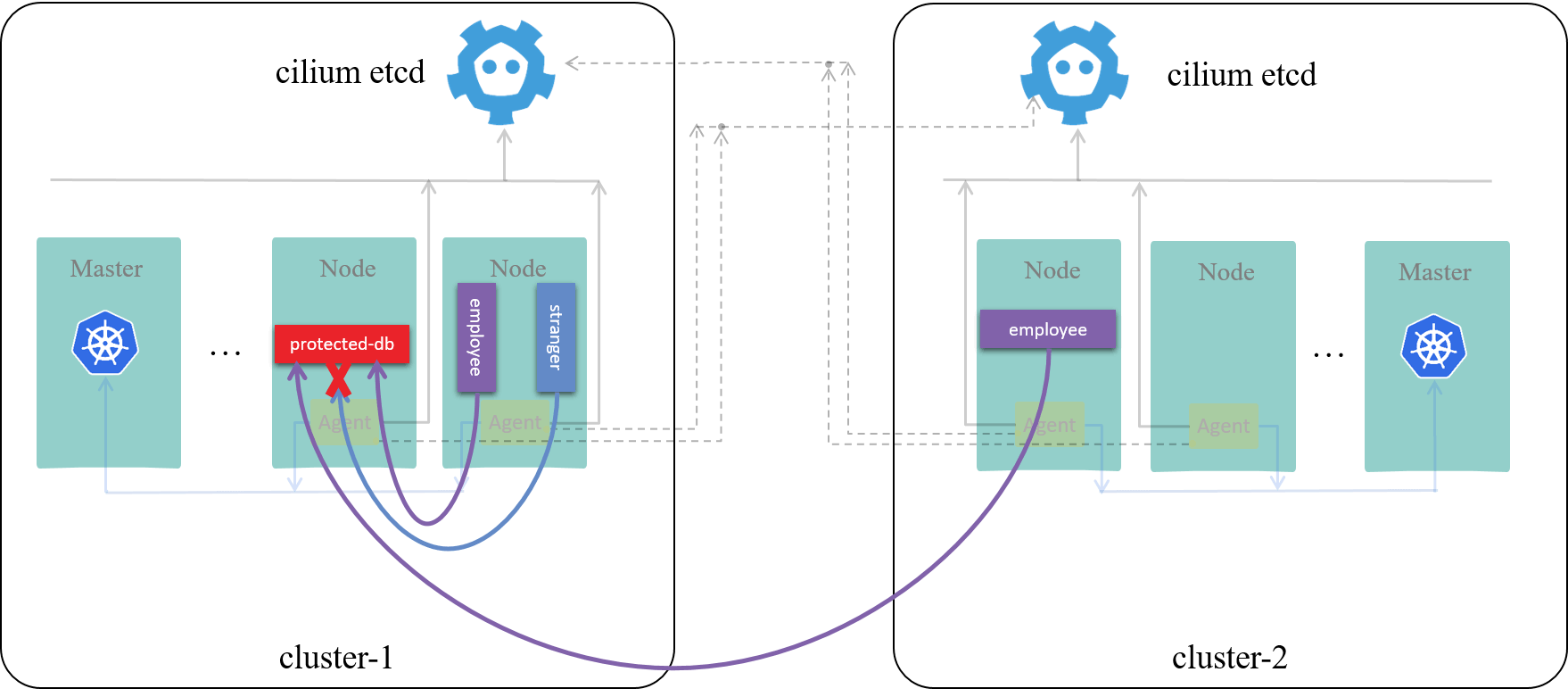

thus, when traffic from remote clusters arrive, the local agent can determine its security context with local knowledge base:

Fig 2-5. Cross-cluster access control with Cilium ClusterMesh [3]

Our hands-on guide [3] reveals how it works in the underlying, refer to it if you are interested.

2.2.2 KVStoreMesh

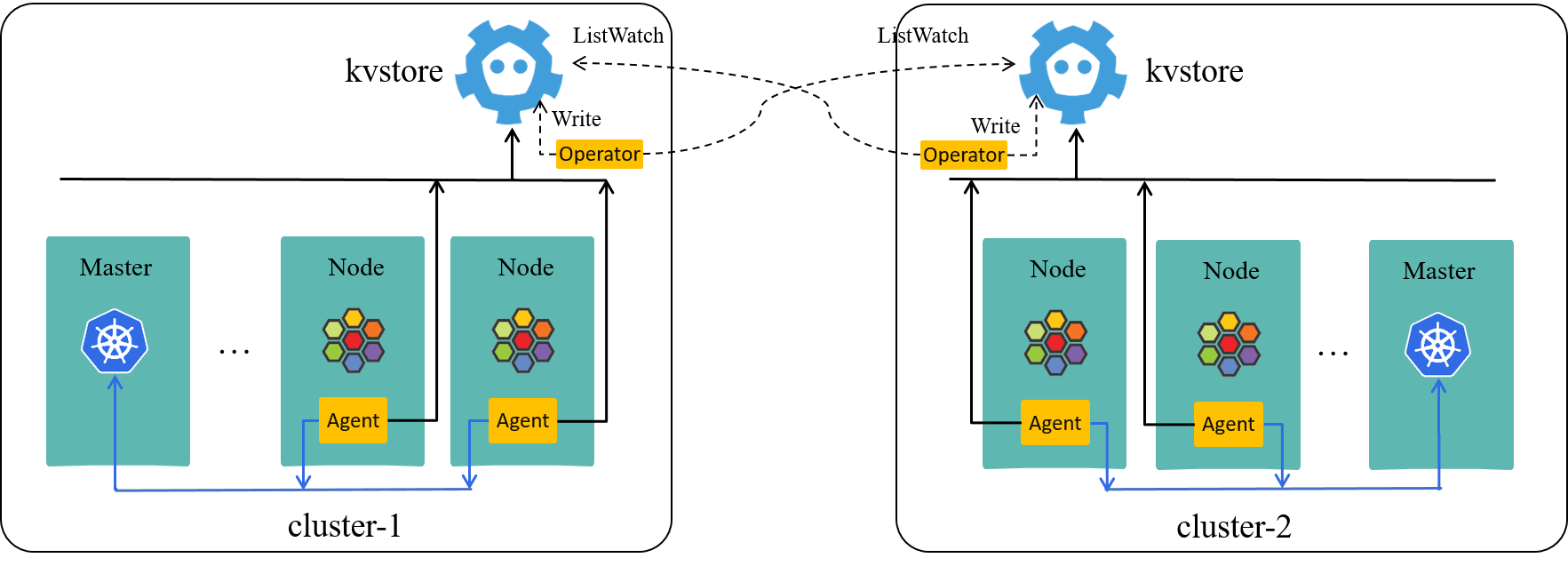

ClusterMesh as a multi-cluster solution is straight-forward, but it tends to be fragile for large clusters. So we eventually developed our own multi-cluster solution, called KVStoreMesh [4]. It’s light-weight and upstream-compatible.

In short, instead of letting every single agent to pull remote identities from

all remote KVStores, we developed a cluster-scope operator to do this, which

synchronizes remote identities to the KVStore of the local cluster.

Putting it more clearly, in each Kubernetes cluster, we run a kvstoremesh-operator, which

- Listen to Cilium metadata (e.g. security identities) changes from all other clusters’ Cilium KVStores, and

- Write the changes to the local Cilium KVStore

The two-cluster case:

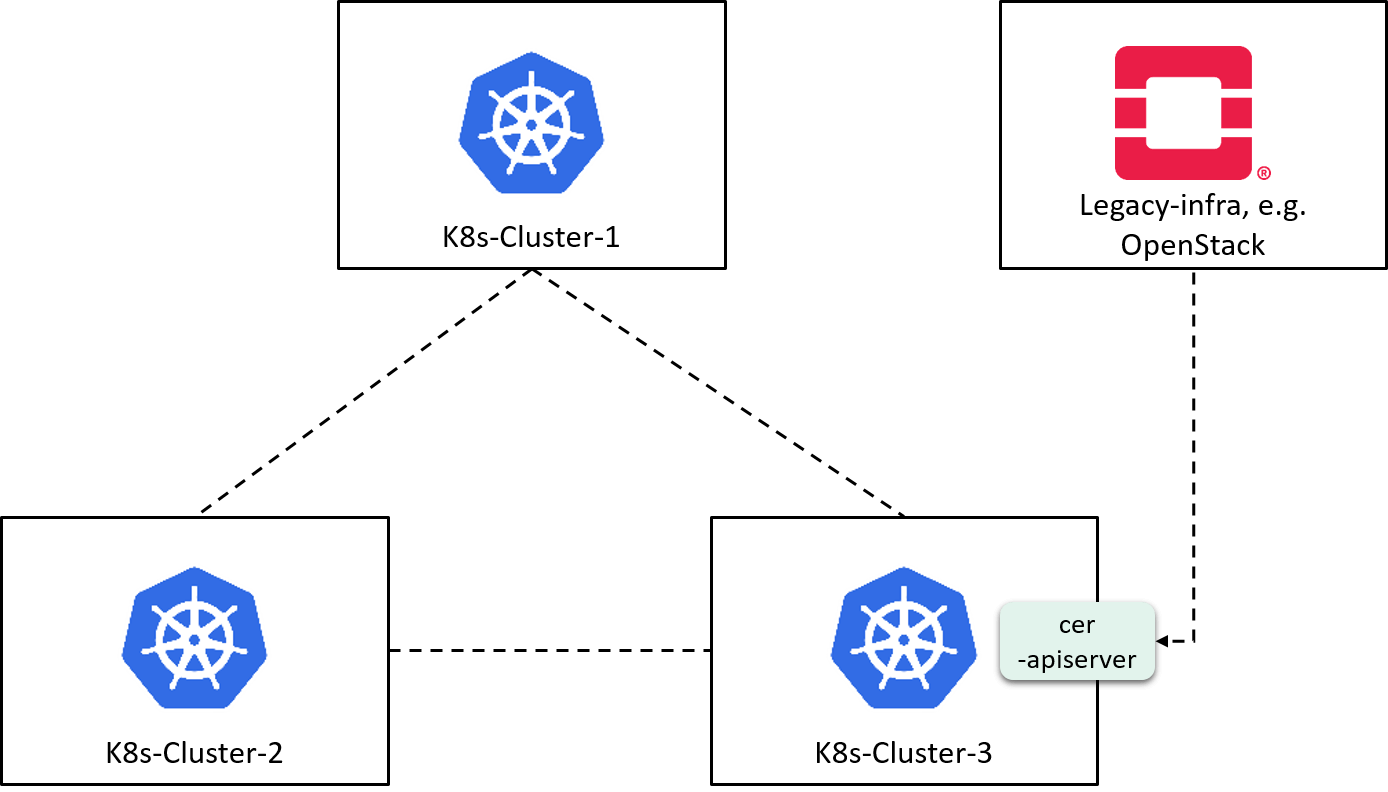

Fig 2-6. Multi-cluster setup with KVStoreMesh [4]

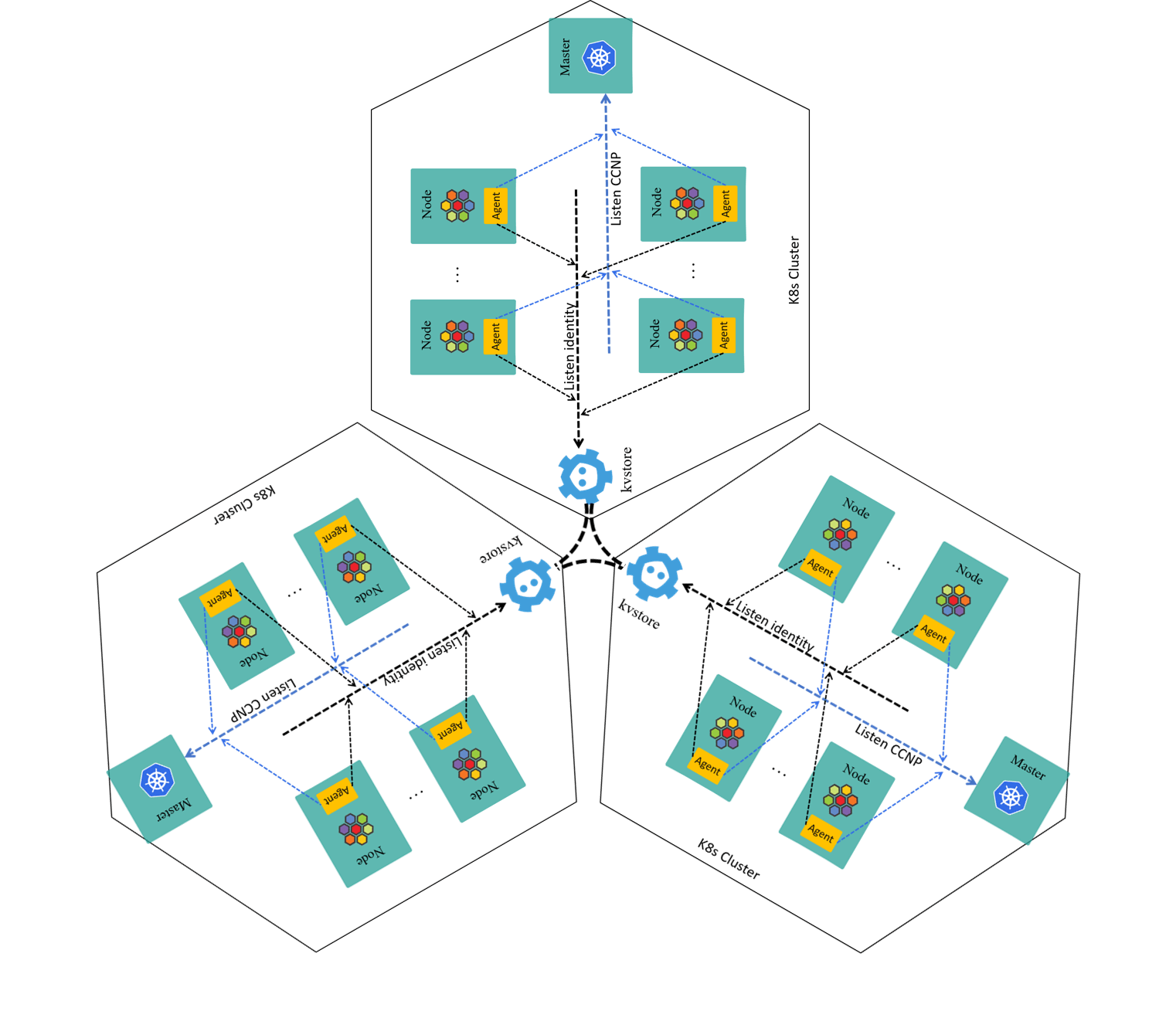

The three-cluster case:

Fig 2-7. Multi-cluster setup with KVStoreMesh (kvstoremesh-operator omitted for brevity)

Technically, with KVStoreMesh, cilium-agents get remote identities from their local kvstore directly. This ensures each cilium-agent to have a flat, global security view of all the pods in all clusters - just as ClusterMesh does, but without suffering from stability and flexibility issues. ClusterMesh vs. KVStoreMesh comparisons will be detailed later.

The excellent design of Cilium makes the above idea work most of the time, and we’ve fixed some bugs (most of which have already been upstreamed, a few are under reviewing) to make the remaining corner cases work as well.

2.3 Policy enforcement over legacy clients

With CNP/CCNP and KVStoreMesh, we’ve solved single-cluster and multi-cluster access control over vanilla cilium-powered-pods. Now let’s go one step further, consider how to support legacy workloads, e.g. VM from OpenStack.

Note that our technical requirement over legacy workload is simplified here: we only consider controlling the legacy workloads when they are acting as clients; for those acting as servers, we regard them to be out of the scope of this solution. This makes a good starting point for us.

2.3.1 CiliumExternalResource (CER)

Based on our understanding of Cilium’s design and implementation,

we introduced a custom extension over Cilium’s Endpoint model:

// pkg/endpoint/endpoint.go

// Endpoint represents a container or similar which can be individually

// addresses on L3 with its own IP addresses.

//

// The representation of the Endpoint which is serialized to disk for restore

// purposes is the serializableEndpoint type in this package.

type Endpoint struct {

...

IPv4 addressing.CiliumIPv4

SecurityIdentity *identity.Identity `json:"SecLabel"`

K8sPodName string

K8sNamespace string

...

}

We named it CiliumExternalResource (CER), to distinguish it from the later community extension CiliumExternalWorkload (CEW).

CEW came with Cilium 1.9.x, and our CER has been rolled out internally since 1.8.x. Comparisons of them will be detailed in the next section.

And the reason why we didn’t name it

ExternalEndpointis that there is already anexternalEndpointconcept in Cilium, which is used for totally different purposes. We will elaborate more on this later.

A CER record is a piece of Cilium-aware metadata stored in KVStore (cilium-etcd) that corresponds to one legacy workload, such as a VM instance. With this hacking, each cilium-agent would recognize those legacy workloads when performing ingress access control for vanilla cilium-powered pods.

2.3.2 cer-apiserver

We’ve also exposed an API (cer-apiserver) to let legacy platforms or tools

(e.g. OpenStack, BM system, Non-cilium-CNI) to feed their workload into

Cilium’s metadata store.

By ensuring synchronously calling cer-apiserver when there are legacy

workload operations (such as creating or delete a VM instance), the Cilium cluster

keeps the latest states of legacy workloads.

2.3.3 Sum up: a hybrid data plane

By combining

- CER (feed external resource metadata into one cluster) and

- KVStoreMesh (pull resource metadata from all other clusters, eventually metadata in all clusters converge to the same),

we build a data plane that crosses cloud native as well as legacy infrastructures, as show below:

Fig 2-8. A hybrid data plane by combining CER and KVStoreMesh

Now all the data plane problems have been solved, we are ready to build the control plane.

2.4 Control plane

2.4.1 Access control policy (ACP) modeling

One of our goal is to make the control plane general enough, even if the

underlying policy enforcement fashion has changed one day (e.g. CCNP phased out),

control plane would suffer no changes (or as little as we could).

So we eventually abstracted a dataplane-agnostic AccessControlPolicy model,

this comes with many benefits:

- Enable the control and data planes to evolve independently

- Enable to integrate different kinds of data planes into a single control

plane, such as eBPF-based CCNP, mTLS-based Istio

AuthorizationPolicy, or even some WireGuard-based techniques in the future.

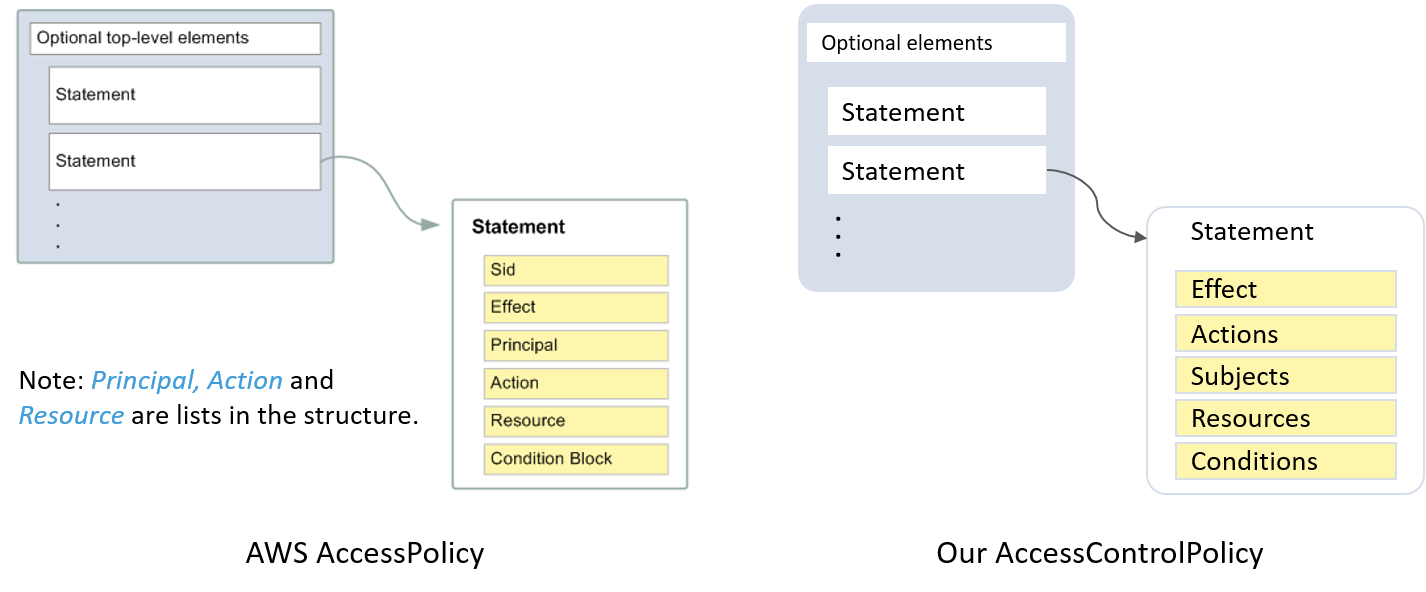

AccessControlPolicy is similar to AWS AccessPolicy

and many other RBAC-based access control models,

all of which are conceptually role based access control [8]:

Fig 2-9. AccessControlPolicy model

Some human-friendly mappings if you’re not familiar with RBAC terms:

- Subjects/Principals -> clients

- Resources -> servers

An example is shown below, which allows app 888 and 999 to access redis cluster bobs-cluster:

kind: AccessControlPolicy

spec:

statements:

- actions:

- redis:connect

effect: allow

resources:

- trnv1:rsc:trip-com:redis:clusters:bobs-cluster

subjects:

- trnv1:rsc:trip-com:iam:sa:app/888

- trnv1:rsc:trip-com:iam:sa:app/889

2.4.2 Enforcer-specific adapters

The dataplane-agnosticism of the control plane requires there should be adapters to transform ACP to specific enforcer formats.

- ACP->CCNP adapter (main use case currently)

- ACP->AuthorizationPolicy adapter (Istio use case, POC verified)

2.4.3 Push (and reconcile) policy to Kubernetes clusters

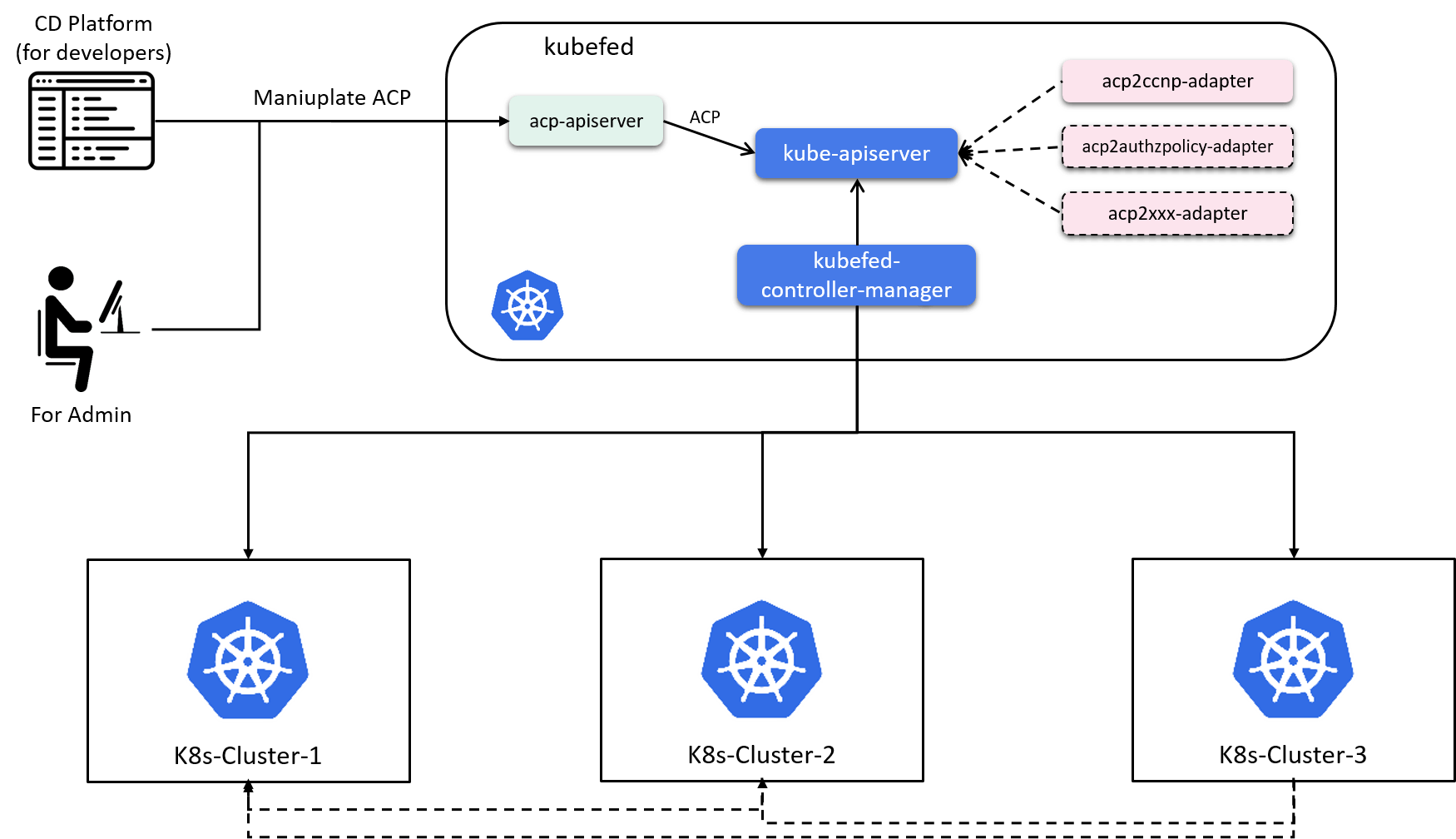

Another piece of the control plane is pushing the transformed dataplane-aware policies into Kubernetes clusters.

We use kubefed (v2) to achieve this goal:

AccessControlPolicyis implemented as a CRD in kubefedacp2ccnp-adapterlistens on ACP resources and transforms them to FCCNP (Federated CCNP)kubefed-controller-managerlistens on FCCNP resources, renders them into CCNP and pushes the latter to the specified member kubernetes clusters in the FCCNP spec.

Now, all the technical pillars for our security cathedral have completed, for example - you could now create an ACP from a yaml file and it will be automatically transformed into FCCNP, then rendered into CCNP and further be pushed to individual Kubernetes clusters - but only if you could access kubefed and know the “raw” yaml, ACP model, etc stuffs.

The real users - business application developers - need an ease-of-use interface without caring about all the background concepts and stuffs as we infrastructure teams do.

2.4.4 Integrate into CD platform

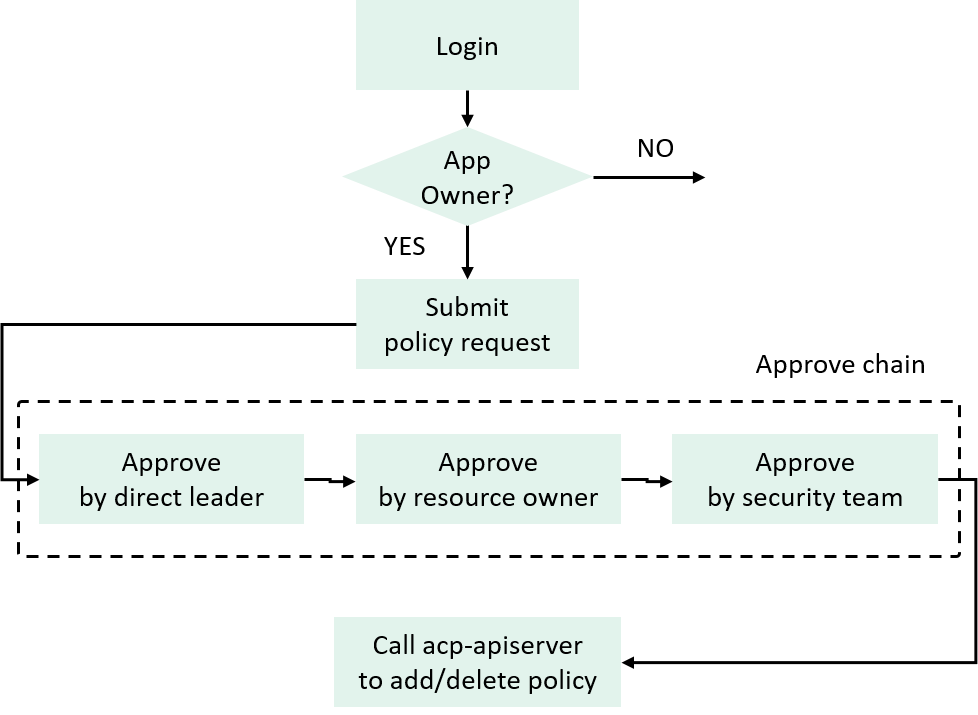

We achieved the goal by integrating the policy manipulation capability and authN/authZ stuffs into our internal continuous delivery platform, which the developers use in daily work.

The AuthN & AuthZ here refer to the validation and priviledge granting stuffs involved during a policy change (add/update/delete) request from users.

Fig 2-10. User side policy request workflow

If a logged-in user is the owner of an application, he/she can submit a request with something like this:

Content: I’m the owner of app

<appid>, and I’d like to access your resource<resource identifier>(e.g. name of a redis cluster).Reason:

<some reason>.

Then the ticket will be sent to several persons for approval, on all approved, the platform calls a specific API to add the policy to the control plane.

Regarding the presentation of the existing policies,

-

Normal user’s view

- Client-side app owner could see which resources the app can access;

- Server-side app owner could seee which client apps could access this resource;

-

Administrator’s view

We also have a dedicated interface for security administrators, which faciliates operations and governing in a global scope.

2.4.5 Sum up: a general control plane

Fig 2-11. High level architecture of the control plane

2.5 Typical workflow

Suppose we have

- A client application with pod label

appid=888(unique per application), owned by Alice, - An in-memory database with pod label

redis-cluster=bobs-cluster(unique per database), owned by Bob,

Then Alice would like her application to access Bob’s database, here will be the workflow:

-

1) Alice

- 1.1) login CD platform

- 1.2) go to the

app 888’s page - 1.3) click “Redis Access Request”,

- 1.4) select the

bobs-cluster, submit request

- 2) Request sends to persons in the approval list

-

3) Request reviewed and approved

- 3.1) Approved by Alice’d direct leader

- 3.2) Approved by Bob

- 3.1) Approved by the security team (if needed)

- 4) CD platform: call the control plane api, add a ACP to kubefed

- 5) ACP added into kubefed

- 6) ACP->CCNP adapter: on listening on ACP added, creates a FCCNP

- 7) kubefed-controller-manager: on listening on FCCNP created, renders a CCNP and pushes to specified Kubernetes clusters (kube-apiserver)

- 8) All cilium-agents in all (CCNP-covered) Kubernetes clusters: on listening

on CCNP created, performs policy enforcement for the pod (if any

redis-cluster=bobs-clusterpod is on the node). CCNP applied.

With all the stuffs illustrated in this section, readers should have had a full view of our technical solution. In the next section, we’ll describe how we’ve rolled out this solution into real environments.

3 Rollout into production

3.1 Capacity estimation

One of the first things when evaluating a security solution is the identity space, or how many security identities does the solution supports.

3.1.1 Identity space

Cilium describes its identity concept in Documentation: Identity. It has an identity space of 64K for a single cluster, which comes from its 16bit identity ID representation:

// pkg/identity/numericidentity.go

// NumericIdentity is the numeric representation of a security identity.

//

// Bits:

// 0-15: identity identifier

// 16-23: cluster identifier

// 24: LocalIdentityFlag: Indicates that the identity has a local scope

type NumericIdentity uint32

Identities of different clusters avoid overlapping by cluster unique cluster-ids.

But what does the 64K mean for us? Enter Cilium’s identity allocation mechanism.

3.1.2 Identity allocation mechanism

The short answer is that Cilium allocates identities for pods with distinguished security relevant labels: pods with the same groups of labels share the same identity.

Fig 3-1. Identity allocation in Cilium, from Cilium Doc

One problem rises here for big clusters: the default label list used for deriving

identities is too fine-grained, which results in

each pod being allocated a separate identity in the worst case -

for example, if you’re using statefulsets, pod-name label will be enlisted,

and it’s unique for each pod, as shown in the below:

$ cilium endpoint list

ENDPOINT IDENTITY LABELS (source:key[=value]) IPv4 STATUS

2362 322854 k8s:app=cilium-smoke 10.2.2.2 ready

k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.cluster=default

k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.serviceaccount=default

k8s:statefulset.kubernetes.io/pod-name=cilium-smoke-2

2363 288644 k8s:app=cilium-smoke 10.2.2.5 ready

k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.cluster=default

k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.serviceaccount=default

k8s:statefulset.kubernetes.io/pod-name=cilium-smoke-3

While this won’t harm the final policy enforcing (e.g. when specifying

app=cilium-smoke in CNP, it will cover all pods of this statefulset), it

prohibits the Kubernetes cluster from scaling: 64K pods would

be the upper bound for each cluster, which is not acceptable for big companies.

This problem can be worked around by specifying your own security relevant labels.

3.1.3 Customize security relavent labels

For example, if we’d like

- All pods with the same

com.trip/appid=<appid>to share the same identity, and - All pods with the same

com.trip/redis-cluster-name=<name>to share the same identity

then we could configure the label option of cilium-agent as this:

reserved:.* k8s:!io.cilium.k8s.namespace.labels.* k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy k8s:com.trip/appid k8s:com.trip/redis-cluster-name

With this setting, all pods with label com.trip/appid=888 (and in the same

cluster with the same serviceaccount) would share the same identity

(the another two labels are automatically inserted by Cilium agent):

$ cilium endpoint list

ENDPOINT IDENTITY LABELS (source:key[=value]) IPv4 STATUS

2113 322854 k8s:com.trip/appid=888 10.5.1.4 ready

k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.cluster=k8s-cluster-1

k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.serviceaccount=default

2114 322854 k8s:com.trip/appid=888 10.5.1.8 ready

k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.cluster=k8s-cluster-1

k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.serviceaccount=default

So with a curated label list, you can support hundreds of thousands of Pods in a single Kubernetes cluster. More information on security labels, refer to Documentation: Security Relevant Labels.

3.2 Business transparency

Technically, one of the benefits of the CNP-based solution is that the entire process of access control is transparent to both clients and servers, which implies that not any client/server changes are needed.

But, does this also imply a transparent rollout into the business? The answer is NO.

To be specific, CNP is a one-shot switch:

- If no policies specified (default), it acts as

allow-any - As long as you created a policy, such as allowing

appid=888to access a resource, then all other clients not in this policy will immediately get denied

which could easily result in business disruptions, as it’s hard to get an accurate initial policy while keeping business users uninvolved if you have just one chance to do this (apply policy).

We solved this problem by applying or refining the policy many times

with the help of policy audit mode. With audit mode enabled and CNP applied,

all accesses that are not allowed by the CNP will be still be allowed but shown as

audit, instead of directly get denied.

Then we can unhurriedly refine our CNP/CCNP by updating those audited client into the CNP.

3.3 Fine-grained policy audit mode toggler

We also would like to have some convenient ways to toggle policy on/off in the control plane, instead of deleting/adding them every time when there are problems or maintaince. Cilium ships with a node-level and an endpoint-level level audit mode configurations configuring via CLI,

# Node-level

$ cilium config PolicyAuditMode=true

# Endpoint-level

$ cilium endpoint config <ep_id> PolicyAuditMode=true

which is a good start but not enough yet.

At the time we were investigating, we noticed a CNP-level policy audit mode had been proposed. It’s on the right way, but there is no clear time schedule (actually haven’t finished till the writing of this post).

3.3.1 Resource-level policy audit mode

As a quick hack, we introduced a resource-level policy audit mode, such as a statefulset is a resource. On toggling audit mode for a statefulset in the control plane, all its pods will be affected (including the newly scaled up ones). We’ve intentionally made this patch compatible with the community, so one day we could drop this hack and move to the CNP-level one.

The implementation:

- Add a controller in kubefed to toggle the audit mode of a resource,

essentially this would modify a specific label on all the pods of the

resource, something like

policy-audit-mode=true/false - Push to member Kubernetes clusters with

kubefed-controller-managerjust as pushing CCNP do - Hacked cilium-agent to respect the policy audit model label.

This function is implemented as an optional feature, so we could include it in/out with a cilium-agent configuration parameter. When configure it as off, cilium-agent would fall back to the community behavior and just ignore the labels.

3.3.2 Survive reboot (keep config)

Changes to the agent were small, as we reused the endpoint-level audit on/off code.

But one additional configuration is needed to make the audit mode setting survive reboot.

The good news is that cilium also provides this configuration,

just adding keep-config: true to the agent’s configmap.

3.4 White-list management

Normal ACP should be a [app list] -> specific-resource policy for ingress control, but there

is also [app list] -> * requirement, such as some management tools need to access

all resources.

So we need support wildcard policy, or whitelist. Specifically, we support two kinds of whitelists.

3.4.1 ACP whitelist

An example shown below,

kind: AccessControlPolicy

metadata:

name: management-tool-whitelist

spec:

description: ""

statements:

- actions:

- credis:connect

effect: allow

resources:

- trnv1:rsc:trip-com:redis:clusters:*

subjects:

- trnv1:rsc:trip-com:iam:sa:app/858

- trnv1:rsc:trip-com:iam:sa:app/676

it will be transform into the following FCCNP:

apiVersion: types.kubefed.io/v1beta1

kind: FederatedCiliumClusterwideNetworkPolicy

metadata:

spec:

placement:

clusterSelector: {}

template:

metadata:

labels:

name: management-tool-whitelist

spec:

endpointSelector:

matchExpressions:

- key: k8s:com.trip/redis-cluster-name

operator: Exists

ingress:

- fromEndpoints:

- matchLabels:

k8s:com.trip/appid: "858"

- matchLabels:

k8s:com.trip/appid: "676"

toPorts:

- ports:

- port: "6379"

protocol: TCP

then rendered and pushed to member clusters as CCNP.

3.4.2 CIDR whitelist

Currently we create CIDR whitelist directly via FCCNP:

apiVersion: types.kubefed.io/v1beta1

kind: FederatedCiliumClusterwideNetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: cidr-whitelist-1

spec:

placement:

clusterSelector: {} # Push to all member k8s clusters

template:

metadata:

labels:

name: cidr-whitelist-1

spec:

endpointSelector:

matchExpressions:

- key: k8s:com.trip/redis-cluster-name

operator: Exists

ingress:

- fromCIDR:

- 10.5.0.0/24

toPorts:

- ports:

- port: "6379"

protocol: TCP

- fromCIDR:

- 10.6.0.0/24

toPorts:

- ports:

- port: "6379"

protocol: TCP

3.5 Custom configurations

Our customizations, among which some are directly security-relevant, and some for robustness (e.g. be more resilient to component failures):

allocator-list-timeout: 48hapi-rate-limit: {"endpoint-create":"rate-limit:1000/s,rate-burst:256,auto-adjust:false,parallel-requests:256", "endpoint-delete":"rate-limit:1000/s,rate-burst:256,auto-adjust:false,parallel-requests:256", "endpoint-get":"rate-limit:1000/s,rate-burst:256,auto-adjust:false,parallel-requests:256", "endponit-patch":"rate-limit:1000/s,rate-burst:256,auto-adjust:false,parallel-requests:256", "endpoint-list":"rate-limit:10/s,rate-burst:10,auto-adjust:false,parallel-requests:10"}cluster-id: <unique id>cluster-name: <unique name>disable-cnp-status-updates: trueenable-hubble: truek8s-sync-timeout: 600skeep-config: truekvstore-lease-ttl: 86400skvstore-max-consecutive-quorum-errors: 5labels: <custom labels>log-driver: sysloglog-opt: {"syslog.level":"info","syslog.facility":"local5"}masqurade: falsemonitor-aggregation: maximummonitor-aggregation-interval: 600ssockops-enable: truetunnel=disabled: direct routing withBIRDas BGP agent

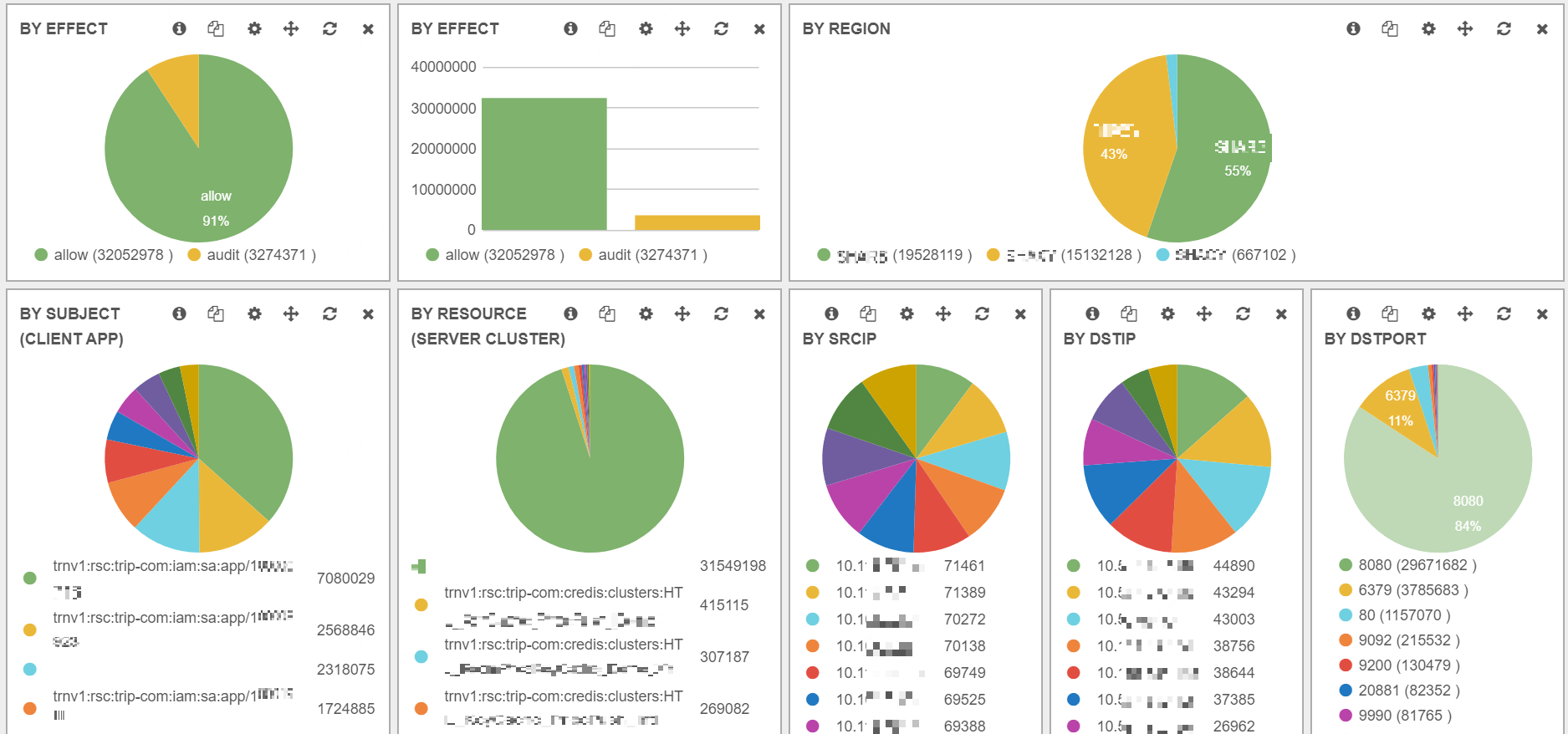

3.6 Logging, monitoring & alerting

- Wrote a simple program to convert hubble flow logs into a

general purpose control plane audit log in real time

- Run as a “sidecar” to each cilium-agent

- Similar to the Hubble adapter for OpenTelemetry release in the recent Cilium v1.11

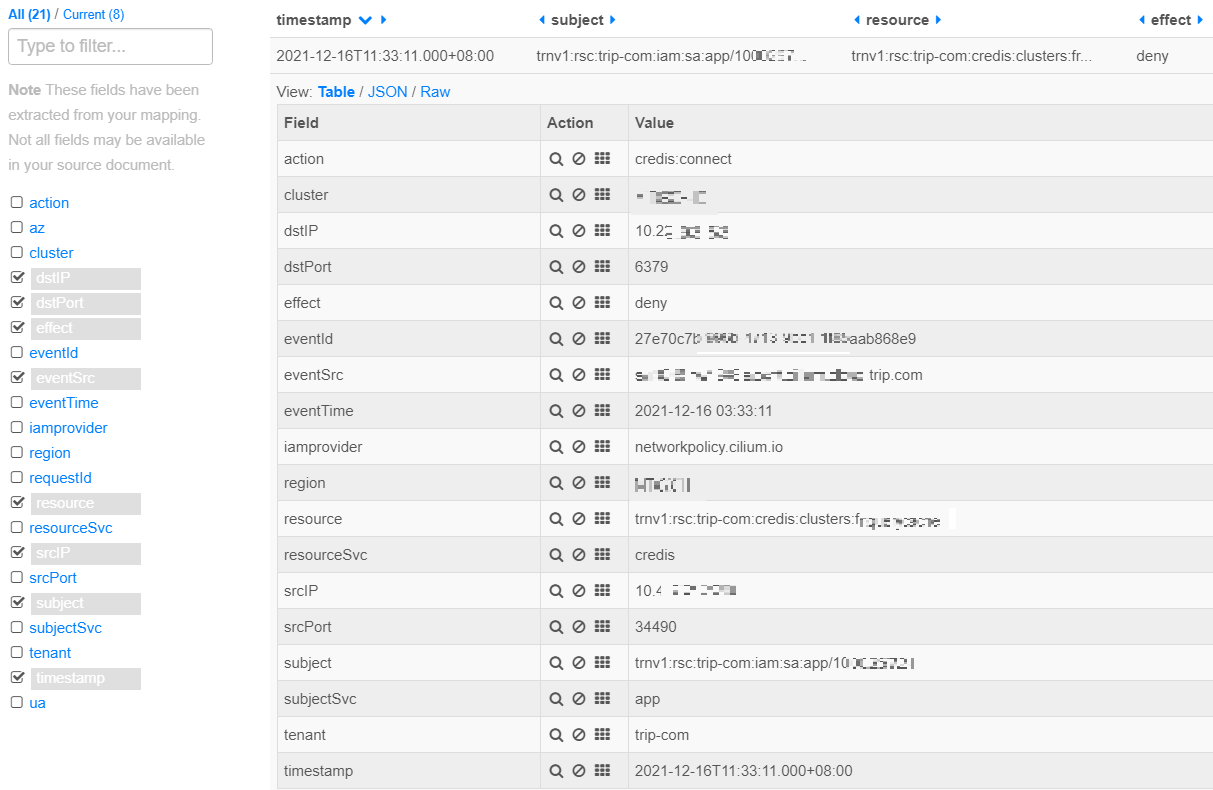

- Send audit logs to ClickHouse, which is also how we aggregated our initial policies for each resource

- Visualize with internal infra (Kibana-based)

- Alerting with internal infra

Fig 3-2. Audit log in our general purpose audit log format

Fig 3-3. Some high-level summaries of audit logs

3.7 Rollout strategy

With all the above discussed, here is our rolling out strategy:

- Enable policy audit mode: audit all, and send audit logs to a central logging infra

- Determine initial policy: run a simple program to aggregate ACP for a specific resource from its history log, and apply the ACP

- Refine initial policy: update ACP if

effect=auditaccesses found for the resource - Publicize the access control plan: let application developers know that access control will be enabled, as well as the self-help policy request procedures integrated in the CD platform

- Formally enable policy: turn off policy audit mode for a resource via resource-level toggler, and all new client applications that would like to access this resource should go through the request ticket process.

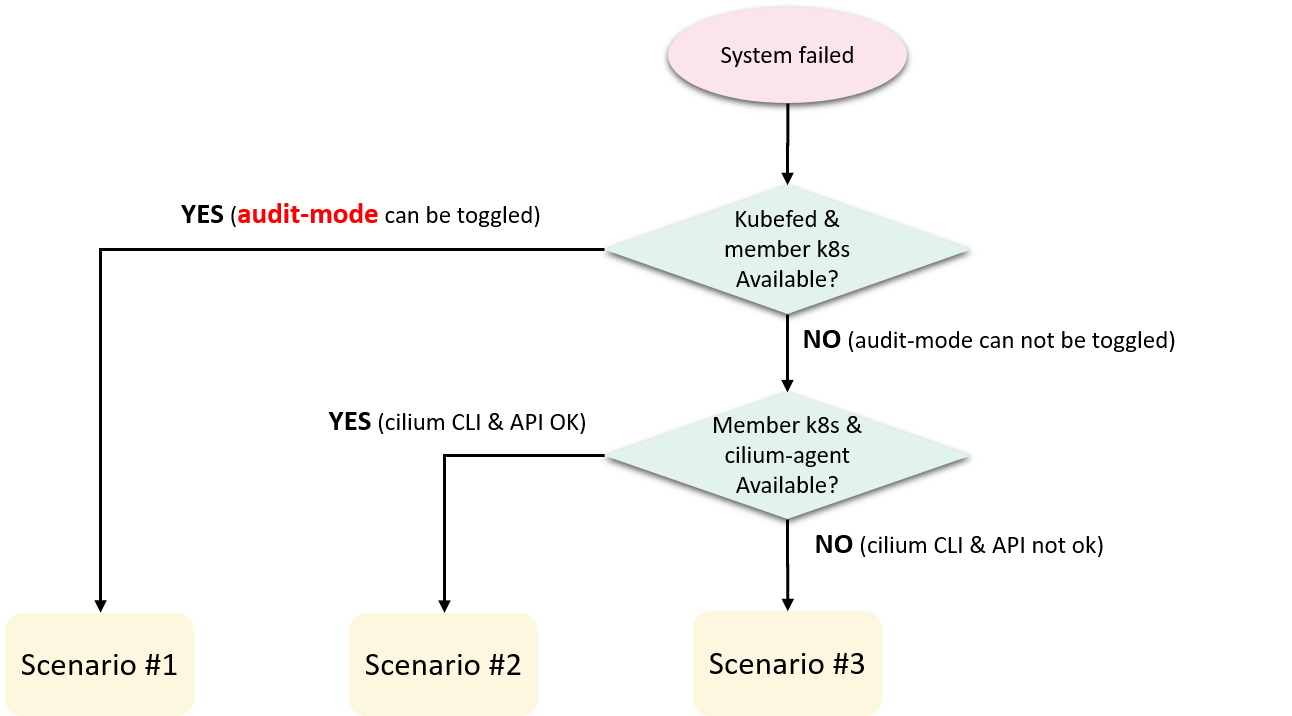

3.8 Downgrade on system failures

One key preparation before rolling out anything into production is the reaction plans for system failures.

We have been using cilium-compose

to deploy Cilium, and here is our down-grade SOP:

Fig 3-4. Downgrade scenarios on system failures

Briefly, when there are system failures that need us to turn off access control, we would react according to three main scenarios:

-

Kubefed cluster and member Kubernetes clusters are ready: we can turn off ACP by toggle resource-level policy audit mode.

-

Kubefed cluster already failed but member Kubernetes clusters are ready, we can

- Disable our resource-level audit feature on cilium-agent, this makes cilium-agent back to community behavior, then

cilium config PolicyAuditMode=trueto open audit mode for all pods on the node

We could do this for a single node, or bulk of nodes with

salt. -

Kubefed cluster and member Kubernetes clusters all failed:

- First completely bring down the cilium-agent (to prevent it from reconcile policies for endpoints), then

- Using

bpftoolto directly write a rawall anyrule for each Pod (endpoint), commands shown below:

# Check if allow-any rule exists for a specific endpoint 3240 root@cilium-agent:/sys/fs/bpf/tc/globals# bpftool map lookup pinned cilium_policy_03240 key hex 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 key: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 Not found # Insert an allow-any rule root@cilium-agent:/sys/fs/bpf/tc/globals# bpftool map update pinned cilium_policy_03240 key hex 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 value hex 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 noexist # Check again root@cilium-agent:/sys/fs/bpf/tc/globals# bpftool map lookup pinned cilium_policy_03240 key hex 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 key: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 value: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00We run the bpftool command in a container created with cilium-agent’s image to avoid any potential version mismatch problems.

3.9 Environments and current deployment status

This solution has been rolled out into our UAT and production environments, and has run over half a year.

Some components’ version:

- Cilium:

1.9.5with custom patches (fixed-ip sts and resource-level-audit-mode) - Kernel:

4.14/4.19/5.10(5%/80%/15%)

Some numbers at the time of this writing:

- 7K+ cilium nodes (baremetal servers), cross multiple Kubernetes clusters

- 170K+ cilium pods

- 40K+ CERs (BM/VM/non-cilium-powered-pods)

- 4K+ CCNPs (scaled down from peak

10K+with some policy aggregation work) - 800K+ flows/minute

CNP features we used:

- L3/L4 rules

- Label selectors

- CIDR selectors

Features we haven’t used:

- L7 rules (only done a POC, wrote a L7 plugin for application-level access control)

- FQDN selectors

- Namespace selectors

4 Discussions

This section discusses some technical questions in depth.

4.1 ClusterMesh vs. KVStoreMesh

ClusterMesh for big clusters has stability problems, which results in cascading failures. The behavior has been detailed in [4], here only shows a typical scenario:

Fig 4-1. Failure propagation and amplification in a ClusterMesh [4]

Following the step numbers in the picture, the story begins:

kube-apiserver@cluster-1fails- All

cilium-agents@cluster-1fail as they can’t connect to kube-apiserver@cluster-1 - All

cilium-agents@cluster-1begin to restart, and on starting, they will connect tokube-apiserver@cluster-1kvstore@cluster-1kvstore@cluster-2

kvstore@cluster-1down, the high volumes of concurrent LisWatch operations from thousands of nodes crashed it (e.g. it was performing backup, already in high IO state),- All

cilium-agents@cluster-1and allcilium-agents@cluster-2down, as they connect tokvstore@cluster-1, - All

cilium-agents@cluster-1and allcilium-agents@cluster-2begin to restart, and similarly, this pose significant pressure on both:kvstore@cluster-1kvstore@cluster-2kube-apiserver@cluster-2

kvstore@cluster-2fails- All

cilium-agents@cluster-1and allcilium-agents@cluster-2down - All

cilium-agents@cluster-1and allcilium-agents@cluster-2begin to restart kube-apiserver@cluster-2crashes, as it can’t serve simultaneous ListWatch from thousands of agents in cluster-2.

Compared with the latter, KVStoreMesh is expected to provide better failure isolation, horizontal scalability, and deploy & maintain flexibility. More information on this topic, refer to [4].

4.2 CER vs. CEW

4.2.1 Pros & cons

- CER is non-intrusive and transparent to legacy workloads. Only a hook is needed to synchronize workloads’ metadata into a Cilium cluster; CEW on the other hand is intrusive to legacy systems, as cilium-agent needs to be installed into each VM, involving considerable changes.

- CER only works when legacy workloads act as clients on Cilium pods’ ingress policy enforcement point, while CEW supports native ingress/egress policy.

4.2.2 Cilium Endpoint vs. CiliumEndpoint vs. externalEndpoint

These three concepts resemble each other a lot in the naming, we try to clarify them a little.

Cilium Endpoint is a node-local concept, and its data is serialized into a local file on the node:

// pkg/endpoint/endpoint.go

// Endpoint represents a container or similar which can be individually

// addresses on L3 with its own IP addresses.

//

// The representation of the Endpoint which is serialized to disk for restore

// purposes is the serializableEndpoint type in this package.

type Endpoint struct {

...

IPv4 addressing.CiliumIPv4

SecurityIdentity *identity.Identity `json:"SecLabel"`

K8sPodName string

K8sNamespace string

...

}

root@node-1 $ cilium endpoint list

ENDPOINT POLICY (ingress) POLICY (egress) IDENTITY LABELS (source:key[=value]) IPv4 STATUS

ENFORCEMENT ENFORCEMENT

139 Disabled Disabled 263455 k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.cluster=cluster-1 10.2.4.4 ready

k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.serviceaccount=default

k8s:io.kubernetes.pod.namespace=default

CiliumEndpoint is a Cilium CRD in Kubernetes:

root@master: $ k get pods cilium-smoke-0 -o wide

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE IP NODE NOMINATED NODE READINESS GATES

cilium-smoke-0 1/1 Running 2 10d 10.2.4.4 node-1 <none> <none>

root@master: $ k get ciliumendpoints.cilium.io cilium-smoke-0

NAME ENDPOINT ID IDENTITY ID INGRESS ENFORCEMENT EGRESS ENFORCEMENT VISIBILITY POLICY ENDPOINT STATE IPV4

cilium-smoke-0 139 263455 ready 10.2.4.4

root@master: $ k get ciliumendpoints.cilium.io cilium-smoke-0 -o yaml

apiVersion: cilium.io/v2

kind: CiliumEndpoint

metadata:

....

status:

external-identifiers:

container-id: 44c4bdb1f0533c6d7cef396

k8s-namespace: default

k8s-pod-name: cilium-smoke-0

pod-name: default/cilium-smoke-0

id: 139

identity:

id: 263455

labels:

- k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.cluster=cluster-1

- k8s:io.cilium.k8s.policy.serviceaccount=default

- k8s:io.kubernetes.pod.namespace=default

named-ports:

- name: cilium-smoke

port: 80

protocol: TCP

networking:

addressing:

- ipv4: 10.2.4.4

node: 10.6.6.6

state: ready

Cilium externalEndpoint is an internal structure holding all the

endpoints in remote clusters in ClusterMesh setup.

For example, if cluster-1 and cluster-2 setup as a ClusterMesh, then all

endpoints in cluster-2 will be shown as externalEndpoint in

cluster-1’s cilium-agents.

// pkg/k8s/endpoints.go

// externalEndpoints is the collection of external endpoints in all remote

// clusters. The map key is the name of the remote cluster.

type externalEndpoints struct {

endpoints map[string]*Endpoints

}

// Endpoints is an abstraction for the Kubernetes endpoints object. Endpoints

// consists of a set of backend IPs in combination with a set of ports and

// protocols. The name of the backend ports must match the names of the

// frontend ports of the corresponding service.

type Endpoints struct {

// Backends is a map containing all backend IPs and ports. The key to

// the map is the backend IP in string form. The value defines the list

// of ports for that backend IP, plus an additional optional node name.

Backends map[string]*Backend

}

Compared with above three, our CER model might be called NodelessEndpoint:

it re-uses the Cilium Endpoint model, but doesn’t bind to any host as Endpoint does.

4.3 Resource-level vs. CNP-level policy audit mode

We think CNP-level audit mode is the right way to do the job. In comparison, our hack is not a decent solution, as it involves introducing yet another controller to reconcile specific pod labels.

If CNP-level were finished and ready for production use in the future, we’d consider embracing it.

4.4 Carrying identites: async vs. tunnel vs. SPIFFE

Another important thing about Cilium identity hasn’t been talked about: how identity is determined for a packet when the packet arrives to the policy enforcement point? The answer is: it depends.

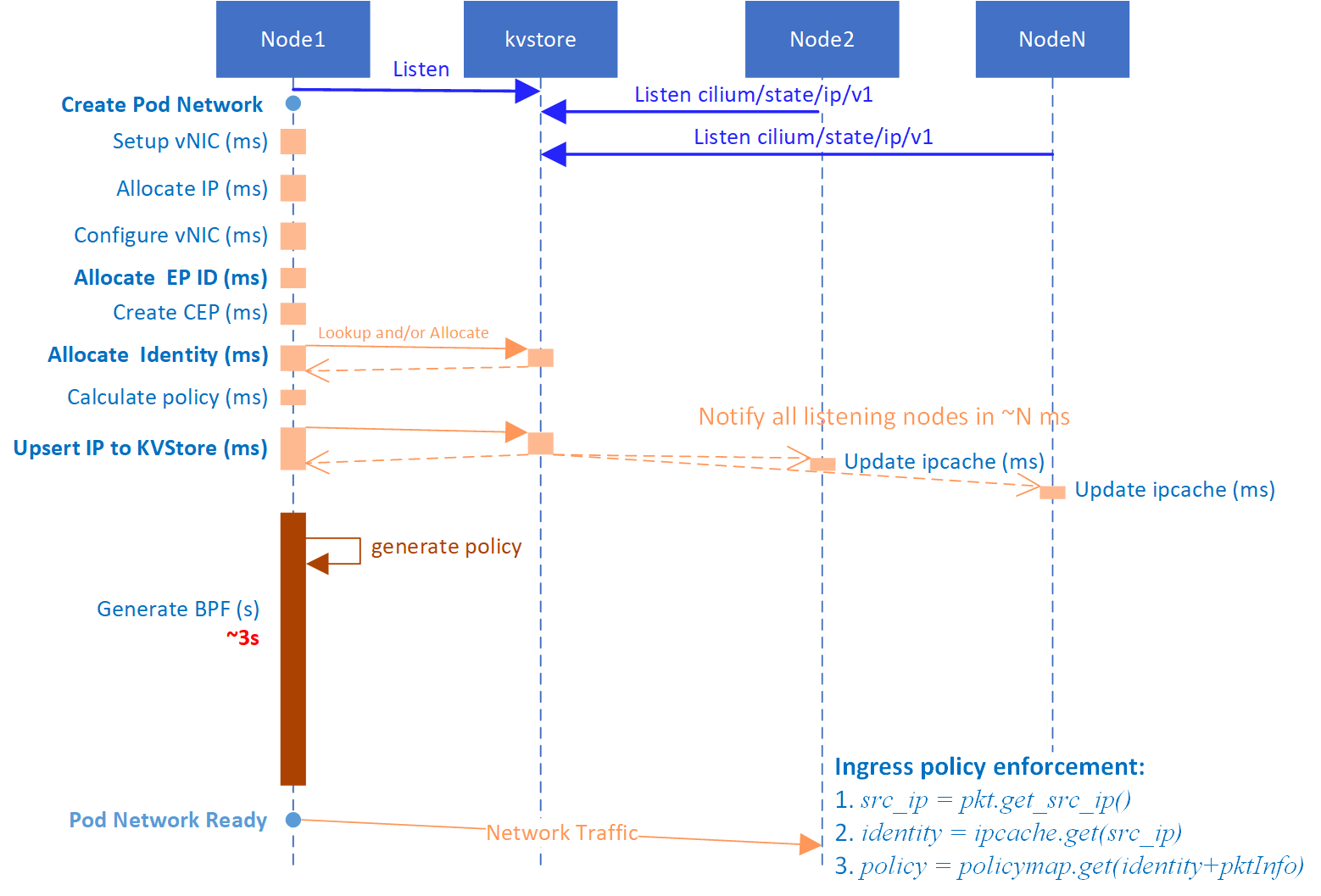

In direct routing mode, Cilium allocates and synchronizes identities via KVStore, below is a brief time sequence showing how identity is synchronized and policy enforced:

Fig 4-2. Identity propagation during Cilium client scale up

The case in the picture:

- Server pods reside on Node2

- A new client pod is created on Node1

The picture tries to illustrate how client pod's identity arrived to Node2 before its packets' arrival. Theoretically, there are possibilities that the identity arrives after packets, which would result in immediate denies.

Relevant calling stacks [9]:

__section("from-netdev")

from_netdev

|-handle_netdev

|-validate_ethertype

|-do_netdev

|-identity = resolve_srcid_ipv4() // extract src identity

|-ctx_store_meta(CB_SRC_IDENTITY, identity) // save identity to ctx->cb[CB_SRC_IDENTITY]

|-ep_tail_call(ctx, CILIUM_CALL_IPV4_FROM_LXC) // tail call

|

|------------------------------

|

__section_tail(CILIUM_MAP_CALLS, CILIUM_CALL_IPV4_FROM_LXC)

tail_handle_ipv4_from_netdev

|-tail_handle_ipv4

|-handle_ipv4

|-ep = lookup_ip4_endpoint()

|-ipv4_local_delivery(ctx, ep)

|-tail_call_dynamic(ctx, &POLICY_CALL_MAP, ep->lxc_id);

Tunnel (VxLAN) mode embeds identity into the tunnel_id field

(corresponding to the VNI field in VxLAN header) of each single packet,

so the above-mentioned deny scenario would never happen:

handle_xgress // for packets leaving container

|-tail_handle_ipv4

|-encap_and_redirect_lxc

|-encap_and_redirect_lxc

|-__encap_with_nodeid(seclabel) // seclabel==identity

|-key.tunnel_id = seclabel

|-ctx_set_tunnel_key(&key)

|-skb_set_tunnel_key() // or call xdp_set_tunnel_key__stub()

|-bpf_skb_set_tunnel_key // kernel: net/core/filter.c

There is also an issue tracking SPIFFE (Secure Production Identity Framework for Everyone) support in Cilium, which dates back to 2018, and still ongoing.

4.5 Performance concerns

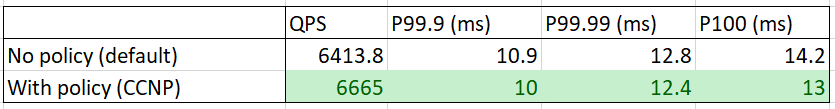

Perhaps the most surprising piece with Cilium-powered network policies is: enabling CNP will not slow down the dataplane - on the opposite, it will increase the performance a little bit! Below is one of our benchmarks:

where we could see that after an ingress CCNP is applied to a server pod, its QPS increases, as well as latency decreases. But why? The code tells the truth.

If no policy applied (default), Cilium would insert a default allow-all

policy for each pod:

|-regenerateBPF // pkg/endpoint/bpf.go

|-runPreCompilationSteps // pkg/endpoint/bpf.go

| |-regeneratePolicy // pkg/endpoint/policy.go

| | |-UpdatePolicy // pkg/policy/distillery.go

| | | |-cache.updateSelectorPolicy // pkg/policy/distillery.go

| | | |-cip = cache.policies[identity.ID] // pkg/policy/distillery.go

| | | |-resolvePolicyLocked // -> pkg/policy/repository.go

| | |-e.selectorPolicy.Consume // pkg/policy/distillery.go

| | |-if !IngressPolicyEnabled || !EgressPolicyEnabled

| | | |-AllowAllIdentities(!IngressPolicyEnabled, !EgressPolicyEnabled)

And when looking for a policy for an ingress packet, here is the matching logic:

__policy_can_access // bpf/lib/policy.h

|-if p = map_lookup_elem(l3l4_key); p // L3+L4 policy

| return TC_ACK_OK

|-if p = map_lookup_elem(l4only_key); p // L4-Only policy

| return TC_ACK_OK

|-if p = map_lookup_elem(l3only_key); p // L3-Only policy

| return TC_ACK_OK

|-if p = map_lookup_elem(allowall_key); p // Allow-all policy

| return TC_ACK_OK

|-return DROP_POLICY; // DROP

The matching priority:

- L3+L4 policy

- L4-only policy

- L3-only policy

- Allow-all policy

- DROP

As can be seen, default policy has a priority only higher than DROP.

If CNP is applied, the code will return early than in default policy case, and

we think that explains the performance increase.

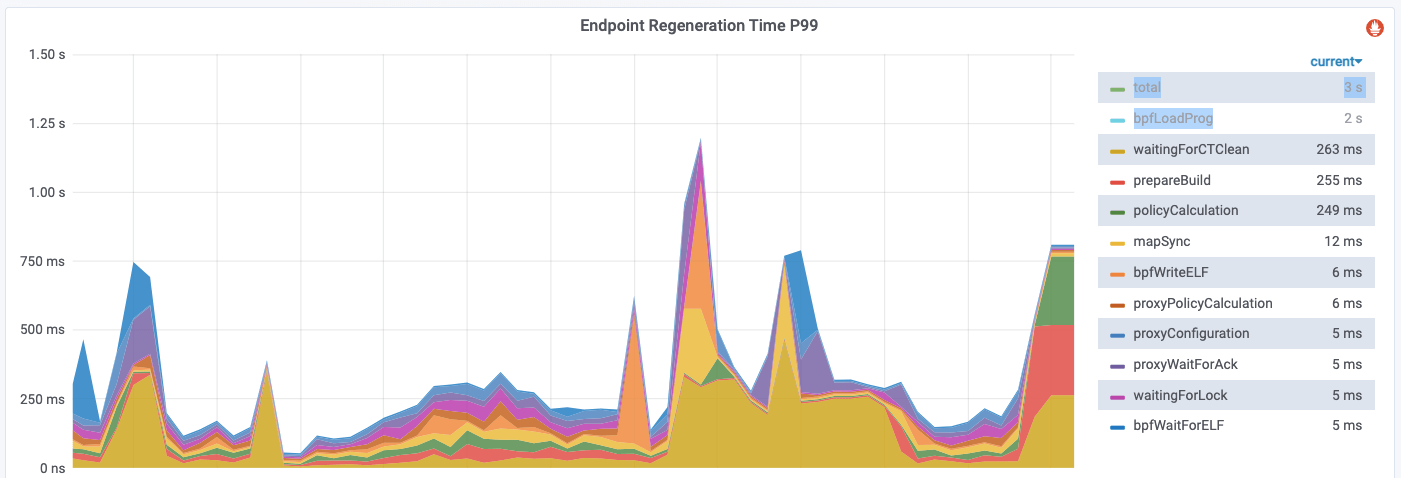

4.6 Frequent BPF regenerations

When a pod is created, a new identity might be allocated. On receiving an identity create event, all cilium-agents would regenerate BPF for all the pods on the node to respect the identity, which is a fairly heavy operation, as compiling and reloading BPF for just a single pod would take several seconds.

Identity creation event would trigger immediate BPF regenerations, but deletion event would not, as identity deletion by designed goes through GC.

Then we may wonder, most pods in the cluster should be irrelevant with the newly created identity, regenerating all pods for every identity event (create/update/delete) wouldn’t be too wasteful ( in terms of system resources such as CPU, memory, etc)?

It turns out that for the irrelevant pods, cilium-agent has a “skip” logic:

// pkg/endpoint/bpf.go

if datapathRegenCtxt.regenerationLevel > regeneration.RegenerateWithoutDatapath {

// Compile and install BPF programs for this endpoint

if regenerationLevel == RegenerateWithDatapathRebuild {

e.owner.Datapath().Loader().CompileAndLoad()

Info("Regenerated endpoint BPF program")

compilationExecuted = true

} else if regenerationLevel == RegenerateWithDatapathRewrite {

e.owner.Datapath().Loader().CompileOrLoad()

Info("Rewrote endpoint BPF program")

compilationExecuted = true

} else { // RegenerateWithDatapathLoad

e.owner.Datapath().Loader().ReloadDatapath()

Info("Reloaded endpoint BPF program")

}

e.bpfHeaderfileHash = datapathRegenCtxt.bpfHeaderfilesHash

} else {

Debug("BPF header file unchanged, skipping BPF compilation and installation")

}

Most pods will go to the else logic, which also explains why the regneration time

P99 decreases dramatically after excluding bpfLogProg:

You could double confirm this behavior by watching the bpf object files in

/var/run/cilium/state/<endpoint id> and /var/run/cilium/state/<endpoint id>_next.

We have more technical questions that worth discussing, but let’s stop here, as this article is already too lengthy. Now let’s conclude it.

5 Conclusion and future work

This post shares our design and implementation of a cloud native access control solution for Kubernetes workloads (as well as legacy workloads if they act as clients). The solution is currently used for L3/L4 access control, and with more experiences grasped, we’ll extend the solution to more use cases.

We would like to thank the Cilium community for their brilliant work, and I personally would like to thank all my teammates and colleagues for their wonderful work on making this possible.

In the end, we’d always like to contribute our changes (except inelegant ones) back to the community:

~30bugfixes and improvements upstreamed in the past year,- Some are still under code reviewing.

References

- Network Policies, Kubernetes documentation, 2021

- Cilium example of the L7 policy, 2021

- Cilium ClusterMesh: A Hands-on Guide, 2020

- KVStoreMesh, Cilium proposal, 2021

- Ctrip Network Architecture Evolution in the Cloud Computing Era, 2019

- Trip.com: First Step towards Cloud Native Networking, 2020

- Trip.com: Stepping into Cloud Native Networking Era with Cilium+BGP, 2020

- RBAC like it was meant to be, 2021

- Life of a Packet in Cilium: Discovering the Pod-to-Service Traffic Path and BPF Processing Logics, 2020